|

| Charles IV |

The Emperor’s Visit

In late

December 1377 the Holy Roman Emperor paid a visit to Paris. Charles V wanted to

tighten ties with the empire and his uncle Charles IV. On 22nd the emperor was

met at Cambrai by French nobles and thence escorted to Paris. Philip was among

those who greeted the emperor on his arrival at Senlis. An attack of gout meant that the emperor entered

France’s capital in a litter.

Charles V

was accompanied by Philip and the Dukes of Bar, Berry and Bourbon and others of the nobility and

officials when he rode to meet his uncle. When the two men were finally able to

be private after the ceremonies that followed;

‘They removed their hats and

spoke together with great friendship and joy of meeting.’[i]

At a state

occasion on January 6th Philip and his brother of Burgundy served

wine and spices to the emperor and their brother after a banquet for 800 guests

and entertainment by minstrels. The company then all transferred to the Hall of

Parlement where a spectacle representing the taking of Jerusalem during the first crusade was on offer.

|

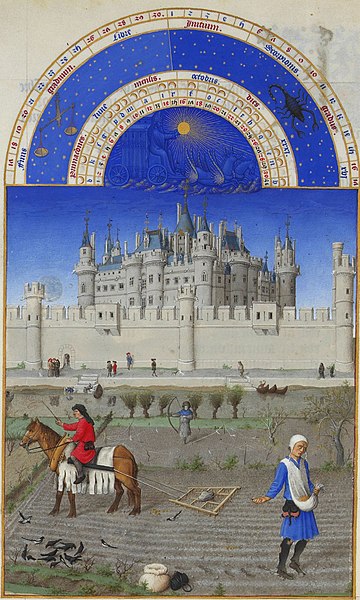

| The Louvre |

The

following day a boat constructed like a residence with ‘halls, chambers, fireplaces and chimneys’ carried King Charles and

his guest down to the new palace of the Louvre which had been modernised from an ancient fortress. In between all the

festivities the two monarchs held private talks.

The final

occasion for the emperor’s visit was the laying out of the case against

England. Charles V was concerned about

‘The lies the English were

spreading in Germany.’[ii]

He spoke for

two hours tracing the causes of the quarrel but no concrete alliance resulted

from the speechifying or the private talks. The visit did being some benefit;

honouring and enhancing France’s reputation.

Death of a King

In the

summer of 1380 Thomas of Woodstock[iii], decided to take the long way round

to support English troops in Brittany, taking his army through Champagne and

Burgundy. Accompanied by such luminaries as Sir Robert Knollys and Sir Hugh Calveley, Thomas cut a swathe across France, closely shadowed by

French knights and soldiers to hamper foraging. Nevertheless, when the citizens

of Rheims refused to succour them, the English burnt 60 villages surrounding

the city.

|

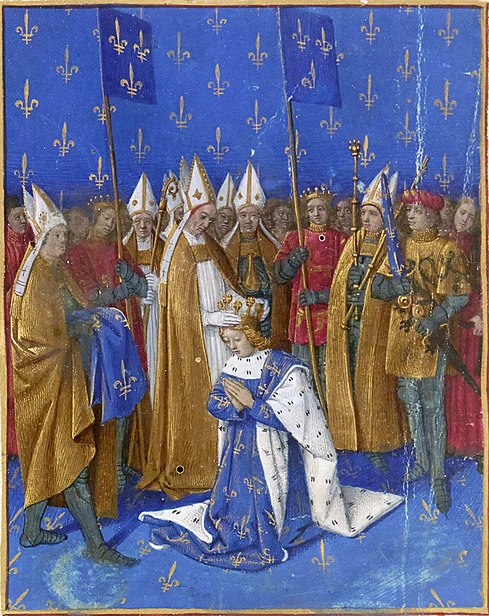

| Coronation of Charles VI |

Philip

commanded two thousand knights, ready to ignore Charles V’s order not to engage

in direct confrontation with the English. He was called away from his command

on his brother’s orders. Charles knew his end was nigh and called for his

brothers and his brother-in-law to attend him at his favourite chateau at Beauté-sur-Marne. He was concerned about his part in

the schism in the church and his taxations of his people.

He died on

16th September 1380 and Philip became one of the council of four

regents, made up of the uncles of the new eleven year old king Charles VI, along with the dukes of Berry,

Anjou[iv] and Bourbon. Anjou was to

be regent while Philip and Bourbon were to have the care and personal

guardianship of the young king. According to Froissart, on his death bed

Charles;

‘Desired, that if a suitable

match could be found, that his son Charles should be married to some German

lady. In this way the Germans and the French would be drawn into closer

alliance.’[v]

The three

brothers and Bourbon quarrelled about Charles’ directions and eventually a

compromise was reached wherein Anjou became president of the regency council. Anjou

was more concerned about a projected expedition to Naples where he planned to seize the kingdom. The actual running of

the country was left to Charles V’s officials known as les Marmousets. Philip had control of northern

France while Berry was lieutenant of southern France.

Insurrection in France

|

| Abbey of St Ouen church |

As Charles V

had feared his brother Anjou’s determined pursuit of money instigated the Harelle tax revolt in 1382[vi]. In January Anjou had

instigated new sales taxes on wine, salt and other commodities[vii]. The order had been

issued secretly and the bidding for the post of tax farmer for these new taxes was held behind

closed doors.

As news of

the new taxes spread riots began in Paris, Laôn, Orléans, Rheims and Amiens.

Anjou refused to rescind the order. Violence broke out in Rouen at the end of

February where the vintners were badly affected by the tax on wine.

|

| Chateau de Vincennes |

They worked

the crowd into a rage and the crowd responded by attacking priests, Jews,

pawnbrokers and the homes of all the former mayors of the city. The rich Abbey of St Ouen was also attacked. The riot fell

apart with the arrival of the young king and the leaders of Rouen begged

Charles for pardon and Charles was advised to grant it. The town’s liberties

were revoked and a royal bailiff placed in charge.

Even as the

citizens of Rouen were being pardoned, Paris rose up in revolt. On 1st

March a tax collector was killed for demanding monies off a woman selling

watercress at Les Halles. Crowds attacked the Hotel de Ville and removed the arms[viii] stored there before

running amuck in the city. The nobility and the rich fled to Vincennes and the city gates were closed[ix]. The richer bourgeoisie

mobilised a militia to resist both the rebels and retaliation from the crown

Suppression

of the revolt is attributed to Philip; he, the Chancellor and Enguerrand de

Coucy went to the Porte St Antoine to parley with the revolting Parisians who

demanded an abolition of all levies since the king’s coronation and amnesty for

all rioting. On behalf of the crown Philip, Coucy and the Chancellor agreed to

all the demands. Some of the rioters were executed while fines were levied,

while discontent simmered close beneath the surface.

Helping Out the Family

.jpg) |

| Louis de Male |

In 1380 the

people of Ghent rebelled against their liege lord Louis de Male when he imposed

a tax to pay for a tournament he wished to hold. They refused to pay crying out

against the squandering of tax monies on;

‘The follies of princes and

the upkeep of actors and buffoons.’[x]

Louis besieged

rebellious Ghent which overthrew his dominion following an attack by Louis on

the starving city. Louis only evaded capture by exchanging clothes with his

valet.

Philip van Artevelde[xi] the leader of the insurrection

declared himself Regent of Flanders and the region’s towns surrendered to his

rule. Artevelde

gave himself airs and graces, requiring trumpets to announce his arrival,

wearing miniver and scarlet[xii] and dined off the

count’s silver plate seized as booty.

Louis de

Male turned to his son-in-law Philip for help dealing with his rebellious

subjects. Philip invaded Flanders in November 1382 with his nephew the king and

his co-regents at the head of an army of French nobles and their men, estimated

to be up to 50,000 in total. With the army came the Oriflamme[xiii], to indicate to all that the French

were engaged in a holy war.

|

| Battle of Roosebeke |

The French

defeated the rebel Flemings[xiv] at the battle of Roosebeke on 27th November, during

which Artevelde was crushed to death along with many of his followers. The

young king greeted his victorious warriors and;

‘Welcomed them

joyously and praised God for the victory which, through their efforts, He had

given.’[xv]

Artevelde

had allied with the merchants of England and the following year the pugnacious Hugh le Despenser, Bishop of Norwich[xvi] ostensibly led a crusade to Flanders[xvii]; in reality it was an

expedition by the English in support of the rebels. The expedition was a

failure and Philip took over running the county when his father-in-law died in

1384.

The Peace of Tournai was signed on 18th December

1385. The treaty allowed for Ghent to keep its privileges, there was an amnesty

for the rebels and that Ghent would be free to choose which pope it supported.

However, Ghent was required to give up its treaty with England and recognize

the King of France.

Bibliography

Chronicles –

Froissart, Penguin Books 1968

Europe:

Hierarchy and Revolt 1320-1450 – George Holmes, Fontana 1984

The Fourteenth

Century – May McKisack, Oxford University Press 1997

A Distant

Mirror – Barbara Tuchman, Papermac 1989

Philip the

Bold – Richard Vaughan, Boydell Press 2011

The Flower

of Chivalry – Richard Vernier, Boydell Press 2003

www.wikipedia.en

[i]

A Distant Mirror - Tuchman

[ii]

Ibid

[iii]

The youngest of Edward III’s children

[iv]

Charles was concerned that his brother Anjou would use the French treasury as

his own

[v]

Chronicles - Froissart

[vi]

Anjou’s pursuit of a crown had been forestalled by the murder of Joanna of

Naples; see http://wolfgang20.blogspot.co.uk/2015/04/the-queen-of-naples-ix_29.html

[vii]

To fund his march to Naples

[viii]

3,000 long handed mallets with heads of lead (maillets) used by police which led to the insurrectionists being

known as Mailliotins.

[x]

A Distant Mirror - Tuchman

[xi]

Son of Jacob van

Artevelde, one of the leaders of an insurrection against Louis I of

Flanders in the late 1320s; Artevelde was a merchant

[xiii]

Carried for the first time since Poitiers

[xiv]

Many of whom lacked even basic armour

[xv]

A Distant Mirror - Tuchman

[xvi]

Known as the Fighting Bishop

[xvii]

Flanders and England supported the pope in Rome; at the time the Western

Schism meant that there were two popes, one in Avignon, supported by the

French and one in Rome. Pope

Urban VI in Rome authorised the crusade

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.