War with the French

Finally at the age of twenty-one William

III, Prince of Orange, was invested with the titles that were considered his

heritage by his supporters - Captain General of the Dutch Army for life and

Stadtholder. But William and his tiny army of nine thousand were facing the

might, not of the Spanish, but of the French, whose enormous armies could be

easily supplied from home. William’s ascension to his new position had been

assisted by the tumult caused by the French army’s remorseless march across

Dutch lands. The Dutch responded by blaming those who had led them to date –

Orangist propaganda informed them that the regents were responsible for the

setbacks in the war, by stubbornly refusing to allow William to inherit his

father’s offices. It was popularly felt that if William was made Stadtholder

the English would retire from the fray. Indeed William attempted to do a deal

with his uncle Charles II.

William did nothing to hold back the

Orange pamphleteers, who roused the anger of the crowds against his political

enemies. He refused to publicly clear Johan de Witt & his brother Cornelius

of the crimes of which they were accused. On the 21st June an

attempt was made on the life of Johan, in which he was injured. Johan resigned

his post as Grand Pensionary, replaced by one of William’s supporters Gaspar

Fagel. Cornelius was imprisoned on a charge of treason. On 7th August a letter

from Charles II to William was published, blaming the de Witts & their

supporters for the war; Charles said he was trying to help William gain his

rightful inheritance. Given the letter by William, Fagel had it read in the

States General & the State of Holland, thereby whipping up public animosity

against the de Witt’s party even further.

|

| Death of the de Witt brothers |

Now William had to concentrate on

removing the French from Dutch soil. In November William led his army in an

attack on the French supply lines at Maastricht. In the meantime an alliance

had been forged with Spain & the Holy Roman Empire, both concerned by the

overweening ambitions of Louis XIV. Louis’ armies took Maastricht, while

William failed to take Charleroi by siege (he was too impetuous a leader &

lacked the patience for a successful siege), but the Dutch fleet under de

Ruyter, defeated the English navy three times during 1673.

The English were brought to the

negotiating table by the strength of anti-French & anti-Catholic public

opinion, fomented by William’s English agents. The Treaty of Westminster was

signed on 19th February 1674 bringing about England’s withdrawal

from the war. By the end of the following year the French had left the Dutch

republic, save for Maastricht. Louis now wished to rationalise his northern

frontier. Containment of the French was to exercise William’s mind for the rest

of life. It was his mission in Europe and he took a dim view of anyone trying

to divert him from his life’s work.

|

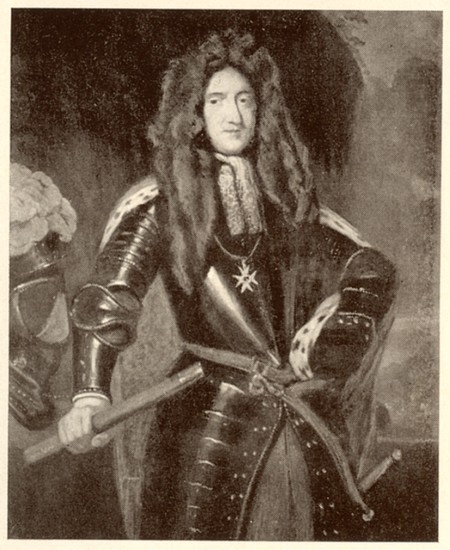

| Count George von Waldeck |

In the early 1670s the Dutch army was

riddled with cowardice, indiscipline & incompetence and William and his

mentor Count George von Waldeck were faced with the challenge of creating a

force able to fight the superior French armies. William’s difficulties as a

general were often compounded by the need to command an composed of allied

nations. The war placed an enormous strain on the Dutch economy & disrupted

trade; with the additional disadvantage that the now neutral English were

profiting from the Dutch problems

In March 1675 William had a fever which

was quickly diagnosed as smallpox. William had no heir. He was the focus of

intense loyalty from the Dutch people and there was no-one else of sufficient

stature for the country to rally round, which could mean disaster for the

nation. The number of people in contact with William was kept to a minimum;

while his friend Bentinck, in accordance with current medical thinking, shared

the bed of his friend, which was believed to draw off the illness from the

patient. By the end of April both William and Bentinck had recovered from the

dread disease.

Many Dutch republicans still feared that

William’s ambition was to create a monarchy. So when he was offered the title

of Duke of Guelderland in 1675 he regretfully had to turn the offer down as the

states of Holland & Zeeland made their opposition clear.

Marriage

In an (ultimately successful) attempt to

bolster his claim to the English throne, William decided to ask for the hand of

Lady Mary Stuart, second in line to the throne; the eldest daughter of the heir

James, Duke of York. William hoped to persuade Charles to secede from his French

alliance and withdraw from the war. It was for this reason that he overcame his

reluctance – the marriage was likely to be unpopular with the Dutch, who had

not cared for William’s mother, another Lady Mary Stuart and William was

contemptuous of the low rank of Anne Hyde, Mary’s mother. Charles II was

persuaded to consider the marriage between his niece and nephew, in an attempt

to quieten the Protestant fears resulting from the 1672 Declaration of Indulgence

and his heir’s Roman Catholicism[i].

With her sister Anne, Mary, who was born

in 1662 (twelve years younger than her future husband) was a declared Child of

the State and their education was the responsibility of the king and his

advisers. Charles guaranteed that they would be brought up as members of the

Church of England, assuring the Protestant succession. Mary’s spiritual mentor

was the Bishop of London – Henry Compton, an outspoken anti-Papist. Lonely and

bored Mary’ emotional output as a teenager was confined to a fourteen year

correspondence with an older acquaintance, Frances Apsley.

In 1673 James, a widower since the death

of Mary & Anne’s mother in 1671, married the fifteen year old Catholic

Princess Mary Beatrice d’Este. The English people and Parliament objected

vociferously to the marriage, but Mary and Anne found a new playmate. By April

1677 the Duchess of York had had two miscarriages, had one daughter die at ten

months old and her daughter Isabella (who was to die in 1681) was a sickly

child. It was also clear that Charles’ marriage was unlikely to produce an

heir, and Charles refused to divorce his barren wife Queen Catherine. The need

to ensure the Protestant succession was becoming imperative. Anti-Catholicism

in England was becoming increasingly stronger.

Charles was inclined to the Dutch marriage

for Mary, as a possible means of detaching his nephew from the Whig opposition

to his government and detaching him from his allies Spain & the Holy Roman

Empire. Charles offered terms to William & in October 1677 William arrived

in England to discuss peace. His reserve alienated the court and Mary was

distressed by the ‘old’ man her relations were planning to marry her to.

William was accompanied by his friend William Bentinck, who was more adept than

William at flattering those whose sense of importance required stroking. James,

whose political sense was never strong, was opposed to the marriage as he hoped

for a Catholic son-in-law – something Parliament would never concede. James’

only support in opposing the marriage came from the French Ambassador.

James reluctantly gave his permission

for the wedding, which was solemnised on 4th November (William’s

birthday) by Bishop Charlton, Mary’s spiritual adviser. The marriage was

enormously popular with the English public, who were hostile to the Anglo-French

alliance and looked forward to an Anglo-Dutch Protestant one. William had

insisted that the marriage take place before peace terms could be discussed, to

avoid his ambitions being taken hostage to his desire for peace. The wedding

was a small private affair, at William’s insistence - he was concerned that a

large ceremony would aggravate his asthma.

The Dutch were not impressed by

William’s choice of bride and the birth of a son to the Duchess of York on the

7th November disappointed William, who was additionally irritated

that he had to stand as Godfather to the child, who now stood between his wife

and the crown. Charles, Duke of Cambridge[ii]

lived only five weeks; he caught smallpox from his half-sister Anne, who’d

visited her stepmother while still convalescent from the disease. William

ordered his wife to stay away from the infected location of St James Palace and

he and Mary quarrelled. William was required in Holland and wanted to return

home.

On 29th November Mary arrived

in the country that was to be her home for the next eleven years. On the 16th

December William and Mary made their state entry into den Haag, before

returning to the palace of Honselaardijk, where William had taken his bride on

their arrival in the Dutch Republic. In private William’s reserve melted away

and Mary was to learn to appreciate William’s good points and to contrast the

vast difference between the Dutch & English courts.

On 29th November Mary arrived

in the country that was to be her home for the next eleven years. On the 16th

December William and Mary made their state entry into den Haag, before

returning to the palace of Honselaardijk, where William had taken his bride on

their arrival in the Dutch Republic. In private William’s reserve melted away

and Mary was to learn to appreciate William’s good points and to contrast the

vast difference between the Dutch & English courts.

William continued to have business

lunches with colleagues and friends, to which Mary was not invited. He worked

in the afternoons, while Mary received visitors. Mary and William had supper

together in the evening. Mary soon realised that her role was to distract

William from the cares of office with talk of gossip and trivia.

For William and Mary marriage came

first. For them, unusual in a political marriage, love followed – according to

some contemporary sources - relatively quickly after the wedding. In March 1678

William had to return to his campaigning against the French. Mary, already in

love with William, wrote to Frances Apsley of her sadness at seeing William

ride away and her worries that she might never see her husband again. In early

April Mary miscarried, probably after a rough trip to Breda to see William.

Peace treaty with the French was finally

signed at Nijmegen on 10th August; the French pushed to the

negotiating table by William’s advance on Mons, with an army of 45,000. Mary by

now believed she was pregnant again. She was delighted by the visit of her

step-mother and sister, accompanied by the Duchess of Monmouth, in October. The

visitors returned to find England in the grip of anti-Catholic hysteria, caused

by Titus Oates’ revelation of the alleged Popish Plot.

Bibliography

The Later Stuarts

1660-1744 – Sir George Clark, Oxford University Press 1985

Queen Anne – Edward

Gregg, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1980

William and Mary – John

van der Kiste, Sutton Publishing 2003

William and Mary – John

Miller, Weidenfeld & Nicholson 1974

The Life & Times of

Charles II – Christopher Falkus, George Weidenfeld & Nicholson 1972

www.de.wikipedia.org

More that I didn't know having only ever covered this period very superficially at school and never having actually read much about it. My sole knowledge of Dutch history is from Baroness Orczy's 'the Laughing Cavalier' and 'The First Sir Percy' so this is an excellent introduction for me to the background of how William of Orange subsequently became joint monarch with Mary.

ReplyDelete